It is easy when a nation is modernizing as rapidly as Burma is to look only forward, rather than backward. Yet, perhaps one of the most important lessons to be learned from the life of Nelson Mandela, who passed away last week, is that while a nation is at a crossroads, attempting to transition into something better than what its most recent past would indicate, it is worthwhile to contemplate where it has been, in addition to where it is going. Otherwise visions of what a future state could be rest on misconceptions, if not outright lies; memories of struggle are easily erased; voices that have already been suppressed become permanently silenced with the passing of time; decades of personal and collective experience are lost; and history becomes a capricious thing—subject to the whims of newly reformed dictators, eager to demonstrate their penitence and good will. In particular, a 2008 New Yorker article comes to mind. Writing about the student leaders of Burma’s 1988 revolt, who in 2008 remained behind bars, each serving sixty-five year sentences, the author writes:

“What Joseph Lelyveld, in his great book Move Your Shadow, wrote of a South African government that had imprisoned and tortured one of Biko’s comrades, is equally true of a Burmese government that has decided to destroy its very best young people: ‘A system that could make the confession about itself that was implicit in the attempt to humiliate and break a young man like this, I thought, showed that it was fundamentally resigned to its own moral rancidness.'” – The New Yorker, 2008

The rancid air of moral depravity and callousness that hung over Burma for so long is finally beginning to lift and the young men referred to in this article, even after surviving decades of imprisonment, remain not only unbroken, but some of Burma’s best hopes for legitimate leadership.

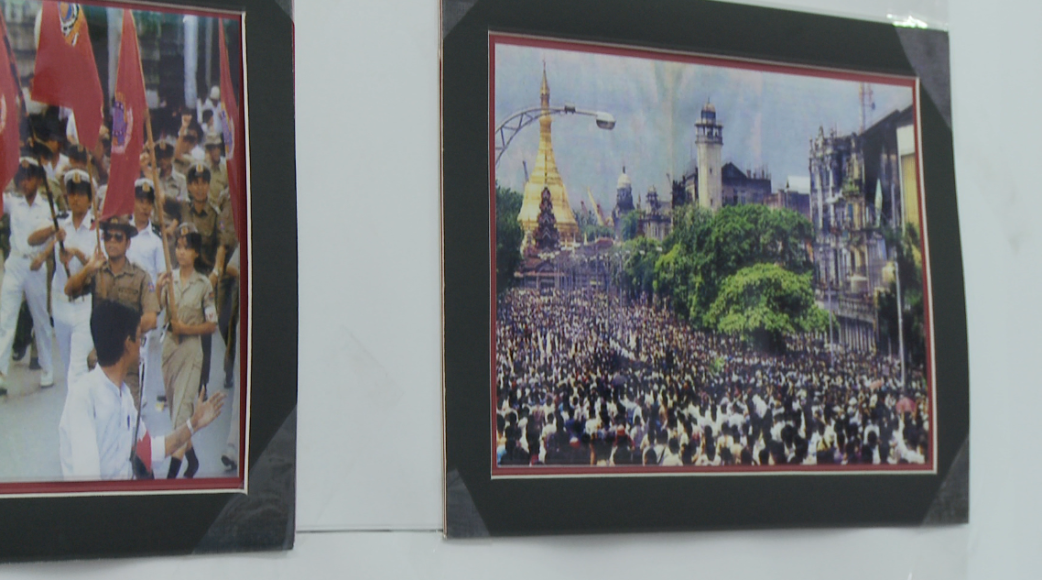

I first encountered the student leaders of the 1988 protests—the 88 Generation as many of them are now known—last March when I was working on a capacity building project in Burma. In retrospect, I knew little about the student leaders who rallied and inspired thousands to take to the streets on August 8, 1988. For many Westerners, the 1988 demonstrations in Burma and the subsequent massacres are inevitably tied to images of Aung San Suu Kyi addressing thousands of onlookers at the Shwedagon Pagoda. Few realize that Aung San Suu Kyi addressed the crowd at the Shwedagon on August 26th, 1988—after planned protests had occurred throughout the spring and summer, culminating in the mass demonstrations on August 8th. Indeed it was the bloody crackdown by the military on civilians that compelled her to take action. Prior to Aung San Suu Kyi’s arrival on the scene, it was student leaders such as Pyone Cho, Min Ko Naing, Ko Ko Gyi, Ant Bwe Kyaw, Mya Aye, and others—undergraduate and graduate students at Yangon University—who organized what is arguably the most significant rebellion in modern Burmese history.

The young men and women—the student leaders of 1988—showed more than the idealism and impetuousness of youth, eager for change. The leaders of 1988 showed true vision, courage, and leadership. They did more than rise up. They organized. They formed alliances. They took responsibility. They were visionaries who offered deep insight. Indeed, their insight often surpassed that of the adults around them (it was the students, after all, who in a crucial moment in 1988 before the September coup, pleaded with Aung San Suu Kyi and others in the ‘adult’ leadership to declare an interim government, rather than to wait for the military to reassert itself).

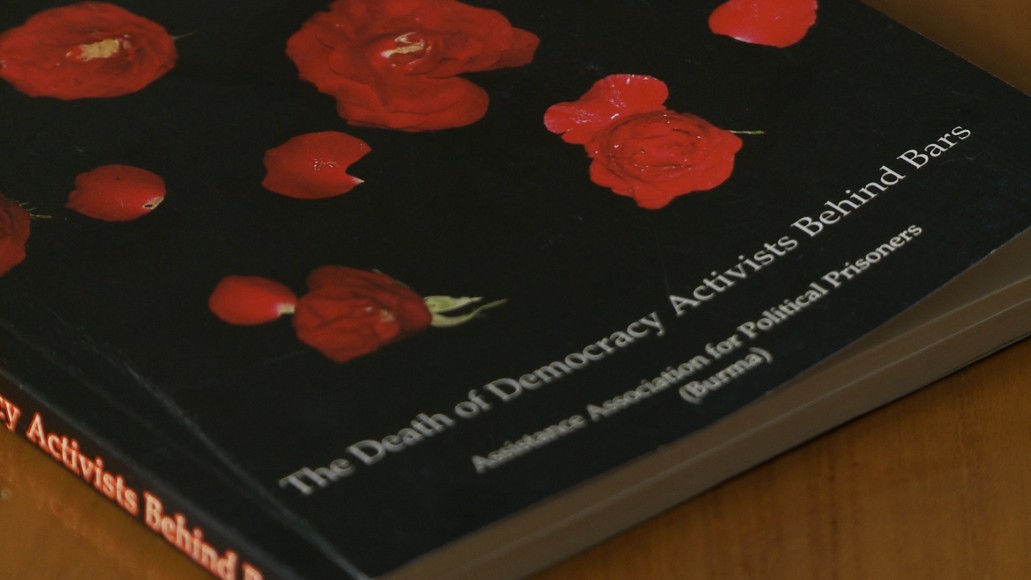

When the coup did occur in September of 1988 and the military gunned down, with what appeared to be cold and calculated precision, thousands on the street, declared martial law, and hurled Burma into what would be decades of political, economic, and cultural isolation, these same young men and women (the ones who survived the massacres) were forced to go into hiding, often in conditions that resembled what victims of persecution endured during Nazi Germany (hiding in the attics and basements of sympathizers for months at a time). By the end of 1989, the main leaders of the 1988 protests had been taken into custody, illegally detained (in some cases for up to two years), and eventually sentenced. Mya Aye and Ant Bwe Kyaw served 8 years in prison. Pyone Cho served 14 years. Min Ko Naing spent 14 years in solitary confinement. The names of other young people, who were arrested, interrogated, tortured, and imprisoned are too numerous to list. Many perished in the prisons.

It is difficult to convey how heavy a nation’s heart becomes when its best, brightest, and most creative young people—the student union president, its vice president—are locked away, seemingly for good.

When many of the student leaders were finally released in the early 2000’s, they began meeting again at local tea shops to discuss politics as they did in their university days. They eventually formed the 88 Generation. At their peril and despite being heavily monitored (I am told that at least one intelligence officer would be standing in front of each of their homes at all times and in 2006 the military government took them into custody and imprisoned them for a period of a few months during the constitutional convention), they continued to engage in numerous peaceful campaigns. Once again, showing vision that surpassed their contemporaries, they encouraged multi-religious dialogue and prayer long before the need to quell interreligious violence in Burma became an international news item and a state priority. Dressed in white (the color of prison uniforms), they visited families of remaining political prisoners to offer support and advocated peacefully for their release. Unlike in neighboring Indonesia, where a veil of silence about past political atrocities is only beginning to lift and the families of those who perished during the massacres were heavily persecuted, the thoughtful leadership and vision of the 88 Generation (both then and now) have allowed families of those massacred during 1988 to remember their loved ones as fallen martyrs, rather than victims. They also continued peacefully and constructively to encourage communities to document abuses and areas of grave neglect by the military government.

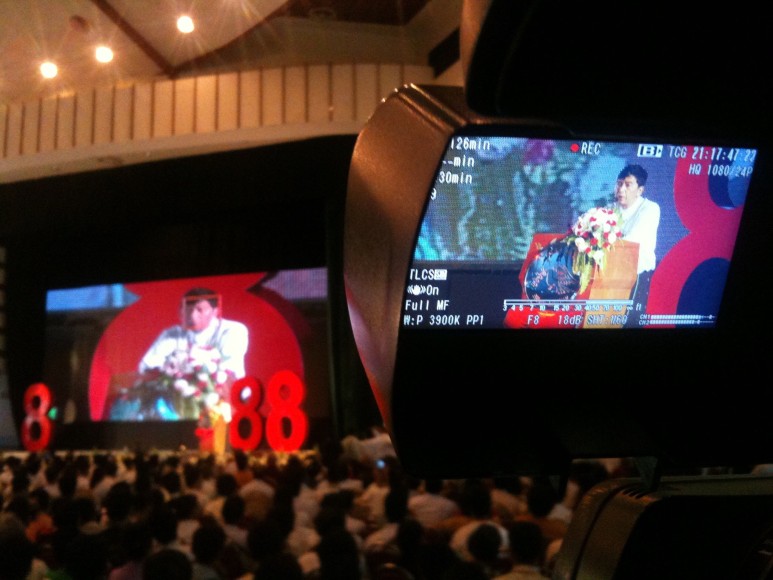

Quite remarkably, the same group of young men and women who organized the 1988 protests also staged the first demonstration that eventually led to the Saffron Revolution in 2007. The leaders of the 88 Generation were subsequently rearrested and each sentenced to over 65 years in prison. They were finally released in January of 2012. Individuals like Pyone Cho had spent 20 years of their adult lives in prison.

Since their release from prison in 2012, the leaders of the 88 Generation continue to mobilize the community and engage in important civil society initiatives. Within a short amount of time, they have reassumed key leadership roles in trying to solve many current social problems facing Burma. Functioning as village elders of sorts to communities all across Burma, they mediate labor disputes, advocate for individuals struggling with the legal system, and work tirelessly to educate communities about their rights, including how to take recourse when those rights are violated. They are currently working to document human rights violations that have occurred over the last several decades. The 88 Generation is typically the first to highlight major issues that are plaguing Burma, whether it is amongst farmers or garment workers. Just within the past year, they have held conferences and encouraged dialogue on issues such as land grabbing, labor negotiations, constitutional reform, and human rights. They have deep, strong connections to the people of Burma, in both urban and rural settings, across ethnic and religious divides. I am told often that the student leaders won the trust and confidence of the people during those crucial months in 1988—something that holds true to this day.

Their strong connection with the Burmese people, both at home and abroad, was evident to me when I had the opportunity to join 88 Generation leaders, Pyone Cho, Ant Bwe Kyaw, and Min Zeyar when they toured the United States in order to connect with the Burmese diaspora community. I sat in on public meetings and participated in their activities for an entire month, as they travelled from city to city. Their travels took them through San Francisco, Los Angeles, Fort Wayne, Washington DC, Chapel Hill, New York City, and Buffalo. In each one of these cities, across all these communities, what I witnessed for each one of the 88 Generation leaders was nothing short of a hero’s homecoming. I witnessed a similar hero’s salute for the leaders of the 88 Generation when I attended the 25th anniversary of the 1988 protests in August. The line of combat for Burma’s hard-fought and hard-won battle for democracy was not in a trench, but in the dark cell of a prison.

These days, there is much to be hopeful about with regard to Burma. Yet, what I find most hopeful is that despite the endless stream of articles and blogs generated by both Western and Burmese media about how it is a reformed-minded benefactor in the form of a now nominally civilian Burmese government that is bequeathing the Burmese people with democracy and ushering them through the gates of freedom; for the average Burmese, the origins of their still limited freedom remain clear, the heroes of the democracy movement remain unchanged.

Whom a society hails as its heroes matters. Heroes matter because they speak to whom we accept as being legitimate leaders. While legitimacy matters in practical terms for who gets elected, heroes also matter because they speak to a society’s notions of ideal forms of personhood—and the Burmese, even in their darkest hours of military rule, held notions about who and what constituted their moral ideal.

While the Burmese notion of what constitutes a good and legitimate leader may change in the coming decades with globalization and exposure to mass media, at least for now, it seems that for many Burmese whom I have spoken to, heroes are not ones who pronounce one set of ideals only to overthrow it for another when it is personally convenient or politically expedient. Heroes are authentic to their sense of self. They show courage. They can envision broader goals for a society and work towards them with patience and conviction even when those goals remain distant, and even if they come at great personal costs to themselves. Such was Mandela and such was his journey—the long walk that he took.

Given the history of the democracy movement in Burma, I felt saddened to read a recent blog by someone who had participated in the 1988 demonstrations, Min Zin. Zin is one of few diasporic Burmese enrolled in a doctoral program in the United States. A regular blogger, Zin’s identity as ‘former freedom fighter’ has afforded him many professional and academic opportunities, including an opportunity in 2003 to meet Nelson Mandela for an event organized by MTV. When Mandela passed away last week, Zin wrote a blog in which he discusses at length his meeting with Mandela and comments on how efforts to move Burma forward is: “stymied by the opposition’s attempt to institutionalize the memory of our past political divisions”. He writes that Mandela’s legacy and the lesson that Burma needs to learn from Mandela is one where “vision and imagination” are emphasized “over history and memory”. Zin’s representation of Mandela’s legacy is completely misleading. He leaves out entirely what was truly Mandela’s contribution to South Africa and to the world—The Truth and Reconciliation Commission that he propelled forward.

Mandela’s journey and his legacy was not one where history and memory were ever sacrificed for supposed vision and imagination. Mandela’s great genius—his vision lay in weaving memory, history, and justice (tempered with much forgiveness) into the future imaginings of a nation—so that it could be better than it was. The 88 Generation’s own legacy remain in marching step with individuals like Mandela.

Please click here to view in Burmese.

လႊတ္လပ္မႈ၏ သူရဲေကာင္းမ်ား – ၿမန္မာၿပည္၏ ၈၈မ်ိဳးဆက္ႏွင့္ မန္ဒဲလားအေမြ | Psycho Cultural Cinema

[…] click here to view in […]