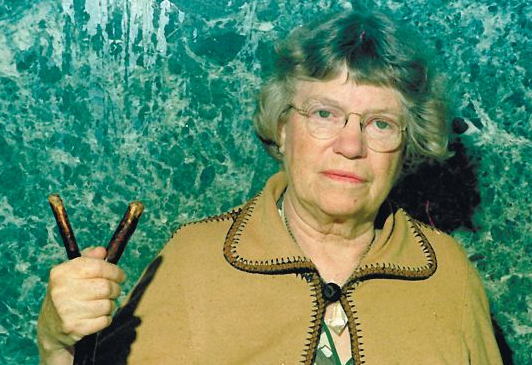

On my recent trip to Bali with anthropologist Rob Lemelson and his film crew, I was asked to reflect upon my early remembrance of Margaret Mead. Mead advised my master’s thesis at Columbia University in the late ‘60s, and offered copies of her films for the comparative analysis of my research on trance. This past month I sat down with her daughter Mary Catherine Bateson to discuss her mother’s early use of photography and 16 mm film.

According to Bateson, when Mead went to Samoa (1926) and later Manus (1929) she took a small number of pictures for illustration with her Brownie camera. It was only after she met her third husband, Gregory Bateson, that photographs and 16 mm film became an essential part of their research technique.

Mead and Bateson had seen footage from Bali and decided that the Balinese would be a good example of a personality type they were particularly interested in investigating. Ruth Benedict’s Patterns of Culture (1934) was pivotal in their understanding of cultural types and piqued their interest in the Balinese character, in particular the opportunity to document an enculturation process that had produced such an artistic and trance-prone character type. Another influence was Robert Flaherty’s films. Man of Aran had been released in 1934 with much publicity and box office success. It was two years later that Mead and Bateson set off for the field with luggage loaded with cameras.

Catherine Bateson: “I don’t think Margaret ever handled a camera, except that Brownie, until after the war. So Gregory was going to do the photography, she the note taking and organize where they were going to go on a given day. She kept the notes in such a form you can recover at the Library of Congress the notes that go with a specific piece of photography. They took 75 rolls of film with them to Bali, of which they used 3 the first day. Having planned to stay 2 years, they totally revised their shooting. In the end they took 25,000 stills with the Leica, and used 22,000 ft. of 16 mm film, which had to be hand wound, developed at the end of each day, and contact prints made. They went with the traditional expectation of taking film that would be illustrative and they found themselves using film in a totally different way. They came back and used the analysis of the film as their analytical and research technique but with the emphasis on the stills. So basically what Balinese Character is, as a book, is a book of photographic plates with captions. Gregory had taken all the photographs, Margaret wrote the captions, but each plate would be illustrative of some theme they had observed in the culture.”

With cameras coming to the forefront as a research technique, there had been an ideological shift, a total paradigm shift of what you do with a camera and what you do with your notes.

As Mead herself stated in the forward to Balinese Character: “We tried to use the still and the moving-picture cameras to get a record of Balinese behavior, and this is a very different matter from the preparation of “documentary” film or photographs. We tried to shoot what happened normally and spontaneously, rather than to decide upon the norms and then get Balinese to go through these behaviors in suitable lighting. We treated the cameras in the field as recording instruments, not as devices for illustrating our theses.”

Mead continues: “We recorded as fully as possible what happened while we were in the (village) houseyards, and it is so hard to predict behavior that it was scarcely possible to select particular postures or gestures for photographic recording. In general we found that any attempt to select for special details was fatal, and that the best results were obtained when the photography was most rapid and almost random.

“The photographic sequence is almost valueless without a verbal account of what occurred, and it is not possible to take full notes while manipulating cameras. The photographer, with his eye glued to a view finder and moving about, gets a very imperfect view of what is actually happening, and MM (who is able to write with only an occasional glance at her notebook) had a much fuller view of the scene than GB. She was able to do some very necessary directing of the photography, calling the photographer’s attention to one or another child or to some special play which was beginning on the other side of the yard. Occasionally, when we were working on family scenes, we were accompanied by our native secretary, I Made Kaler. He would engage in ethnographic interviews with the parents, or take verbatim notes on the conversations.”

Catherine Bateson: “The films didn’t get worked on until the ‘50s. After their divorce, Gregory had left everything with Margaret, and in the ‘50’s she got interested in making teaching films that were comparative, including Bathing Babies in Three Cultures, Childhood Rivalry in Bali and New Guinea, and several films just about Bali including Trance and Dance that was filmed by Jane Belo. These films were produced by Margaret, the voice is hers, but Gregory shot all but the one. The Library of Congress has 22,000 ft. of film and nobody has worked on it since. The way editing was done at that time was with a scissors, and I have been hoping for years to find someone that would take this seriously enough to edit back in the pieces that were taken out of the raw footage to make the teaching films.”

Reflecting on her mother’s career Bateson stated: “When I try to analyze my mother’s career, I think until WWII it was entirely focused on how a human infant is acculturated into a particular culture. If you include Samoa and Bali, it is all about childcare and adult behavior, religion, and performance.”

The details of Mead’s fieldwork could better be captured on film than in her notes, although the latter remained essential to the research, and the photographs and film provided many more opportunities for analysis after leaving the field. How could they have imagined that Mead would edit the footage for teaching films several decades later? There was no turning back.