What is reflexivity?

The question of what “reflexivity” means and why people engage in it has become a question of concern at Elemental Productions. For the past two decades, anthropologist and CEO of Elemental Productions, Robert Lemelson, has been creating a number of films that resulted from person-centered ethnography relating to mental health and culture in Indonesia. This methodology and the resulting body of work are collectively known around the office as “the project.” (Some films included in “the project” are 40 Years of Silence, the Afflictions series, Ngaben, Jathilan, and Standing on the Edge of a Thorn.) Our most recent shoot in Indonesia was mostly in pursuit of a new film, which we are calling the “reflexivity” project. This documentary is imagined to be a “look back” at the work done in the original “project,” an explanation of methodology, and a reflection on the resulting films. This is an ambitious project in that anthropological reflexivity has never been attempted in ethnographic film before. So it is first important to understand what reflexivity is and what purpose it serves among academics.

To answer this question, I turned to leader in the field of Visual Anthropology, Jay Ruby’s, article, “Exposing yourself: Reflexivity, anthropology, and film.” In this article published in Semiotica in 1980, Ruby describes the conspicuous lack of reflexive ethnographic film and calls for anthropological filmmakers to fill the void. A working definition of reflexivity can be pieced together by different excerpts from the Ruby piece:

“To be reflexive, in terms of anthropology, is to insist that anthropologists systematically and rigorously reveal their methodology and themselves as the instrument of data generation.”

“Only if a producer decides to make his awareness of self a public matter and convey that knowledge to his audience is it then possible to regard the product as reflexive.”

“In sum, to be reflexive is to structure a product in such a way that the audience assumes that the producer, process, and product are a coherent whole. Not only is an audience made aware of these relationships, but they are made to realize the necessity of that knowledge.”

As I see it, reflexivity is giving the audience more context surrounding the product (in this case, the dozen-or-so films directed by Lemelson)—meaning who it was produced by and how it was produced. Then, rather than giving the world (or academic community) the product and delivering it as cold, hard facts, the producer is giving the audience a whole array of other factors to consider in their determination of the veracity and neutrality of the product. In any scientific study, being reflexive is disclosing who funded the study, where it was conducted, what instruments were used, what mitigating factors may have been present, biases and allegiances that the researchers themselves may have held, etc. so that the audience is able to not only consume the product (i.e. “findings”), but everything around that product and make a decision for themselves on the neutrality, validity, etc. of the product.

The Intersection of Reflexivity and Documentary Film

Being reflexive in anthropological inquiry and ethnographic writing has become common and is relatively straight-forward. However, being reflexive in documentary film (even if it is geared towards an academic audience) is not as simple. While anthropologists have a scientific duty to demystify their methodology, the conventions of filmmaking generally condemn it. This is just one (of the many) tensions between the aims of anthropologists and filmmakers. In the documentary world, one is supposed to just present the product (i.e.: the film) itself and any information about who made it or how it was made is deemed irrelevant.

“To reveal the producer was thought to be narcissistic, overly personal, subjective and even unscientific. The revelation of process was deemed to be untidy, ugly, and confusing to an audience. To borrow Goffman’s concept (1959), audiences are not supposed to see backstage. It destroys the illusion and causes them to break their suspension of disbelief.”

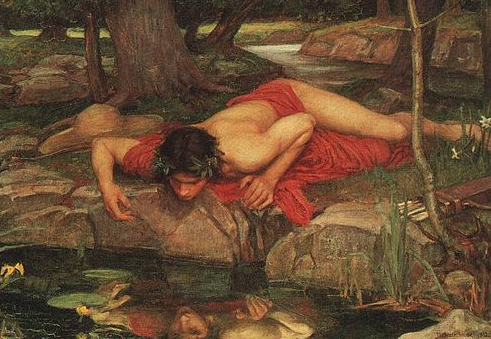

I believe that the criticism of reflexive film being narcissistic is a very important one, and points to fundamental and complex questions that we must ask ourselves before we engage in reflexive ethnographic film. What are we saying by making a film about our achievements, our process, and ourselves? Why are we important? How is what we do unique and innovative? Is our process deserving of a film? Can it be replicated? Can it be learned from? And finally, how does one strike the delicate balance between making oneself the subject of their own inquiry—becoming characters yet retaining the rights to a final edit—and not coming off as egotistical and self-absorbed?

“Echo and Narcissus” John William Waterhouse (1903)

It is very easy to liken a reflexivity film to a “making of” film, and I am still not exactly clear on how they are different, in a technical sense. There is not anything bad about “making of” films, but I do not think that they rise to the caliber of types of impactful films that Elemental Productions aims to make. Jay Ruby even says of such films that their degree of reflexivity is simply present to perpetuate the myths about the genre.

“The audience’s interest in these films is partially based upon the assumed difficulties of production and the heroic acts performed by the makers in the process of getting the footage. These films do not lead an audience to a sophisticated understanding of film as communication, but rather cause them to continue to marvel at the autobiographical exploits of the intrepid adventurer-filmmakers as ‘cinema stars.’”

The Value of Reflexivity

I am finally drawn to the question of whether reflexivity has value in and of itself, or if it only has value in relation to the product it is being reflexive about. In one of our recent meetings the example of The Matrix was brought up. Is somebody going to want to watch The Making of ‘The Matrix’ without having seen The Matrix? Probably not. But yet again maybe so, under certain circumstances. Recently, I watched The Making of ‘The Shining’, a 33-minute video on YouTube shot by the then-17-year-old daughter of the director, Vivian Kubrick. I have never seen The Shining. However, I was captivated by The Making of ‘The Shining’ simply because of its cast of characters. Early on in the film, we are shown Jack Nicholson brushing his teeth. And it is utterly fascinating. I was oddly engaged in his vigorous style of tooth-brushing—hunched over so that his face is inches away from the faucet, he rapidly and repeatedly rinses his toothbrush, delivers a few violent strokes, spits, all the while talking to the camerawoman.

I was totally interested, but solely because it was Jack Nicholson. His celebrity is the reason why I am captivated and absorbed by an intimate moment such as brushing his teeth. My interest in The Making of ‘The Shining’ without having seen the film has nothing to do with the “reflexivity” project. We are not Jack Nicholson. So I am left wondering if people are going to be interested in our reflexivity piece without having seen the films that constitute “the project”? Is reflexivity interesting in and of itself or does one have the have seen the other films to be connected to it? If not, then WHAT about our process appeals to those who haven’t seen the “product”? Basically it comes down to: What is the point of this film? What do we want it to say? And who do we want to say it to? Over the next few months, I anticipate that we will have to answer a number of these complex questions.