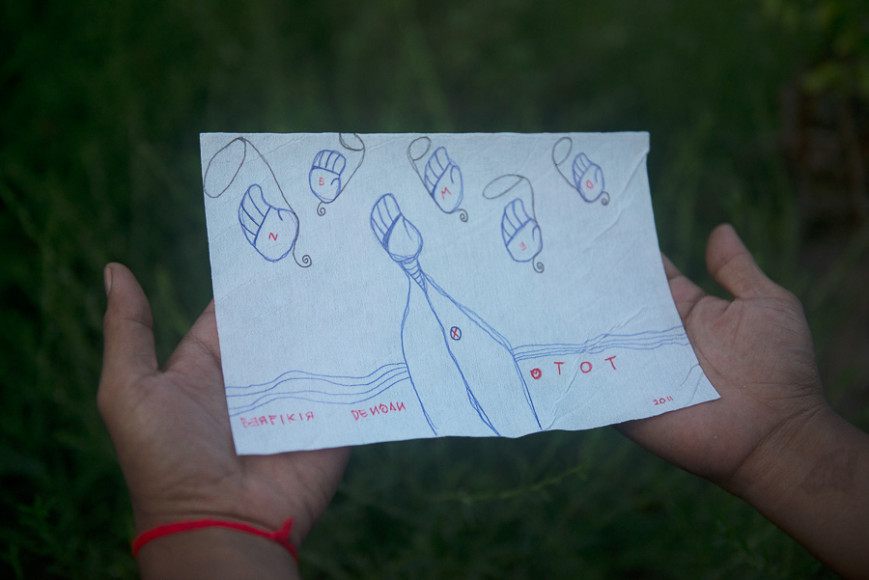

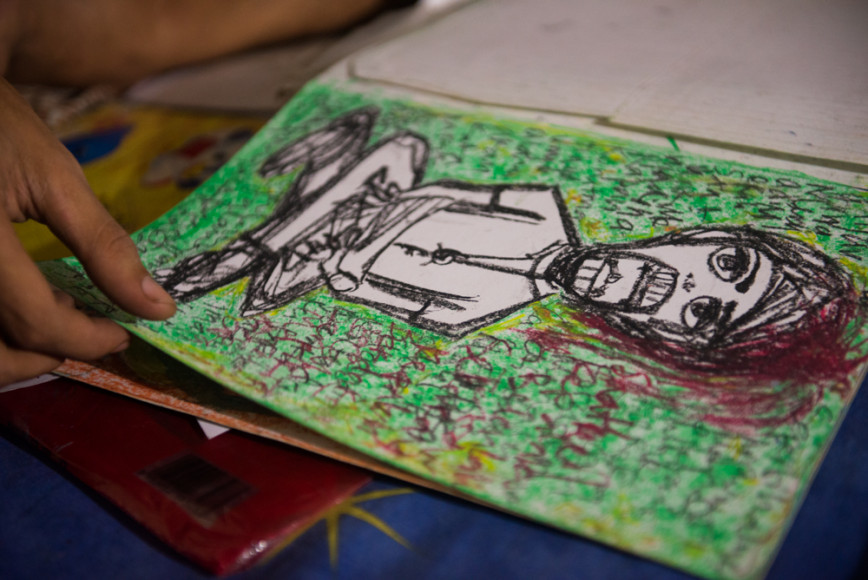

One afternoon in 2014, my friend Mawardi and I were combatting the humid heat with cool, sugary, drinks at a cafe situated in a rice field on the outskirts of Yogyakarta, Central Java. We were looking through some of the artwork he had made over the past few years. I wanted to know more about a small red and black ink drawing.

“This is the first time I celebrated my birthday in prison,” he said. “It’s titled, ‘Happy and Crying.’”

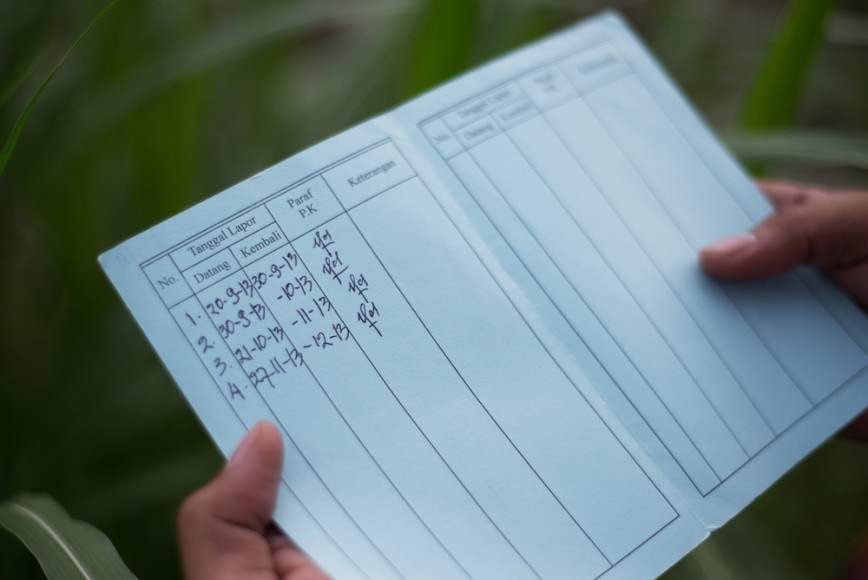

In 2011, when I was living in Indonesia, Mawardi had been imprisoned, receiving a tough sentence for his first drug offense. Visiting him in prison over a number of years and seeing his fellow inmates’ predicaments taught me about the Indonesian prison system and inspired me to learn more. I felt increasingly unsettled by practices I witnessed and read about. Prison sentence lengths were decided depending on bribe amounts and prisoners had to pay for a cell or face daily beatings and electrocution in solitary confinement.

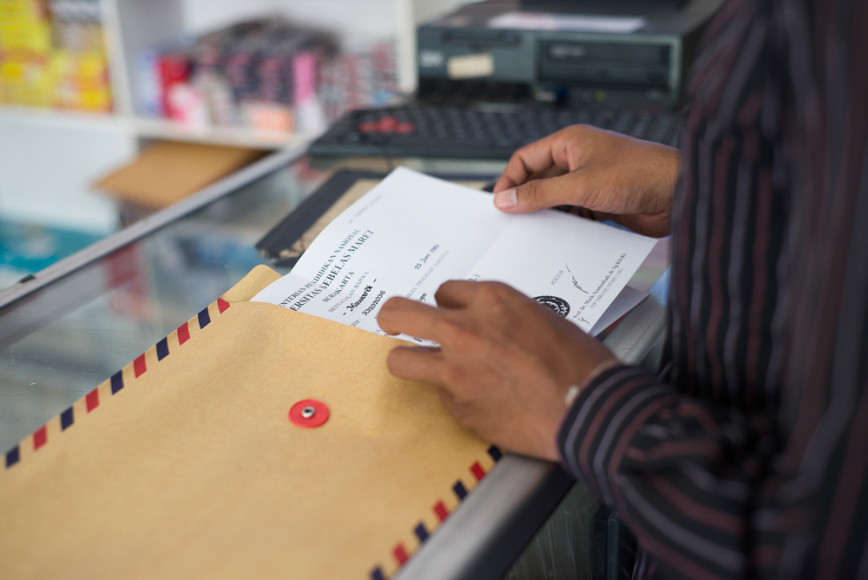

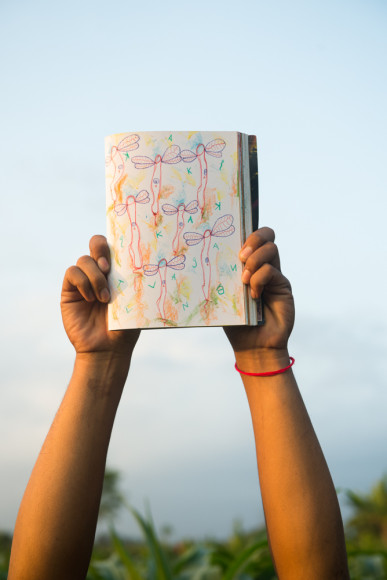

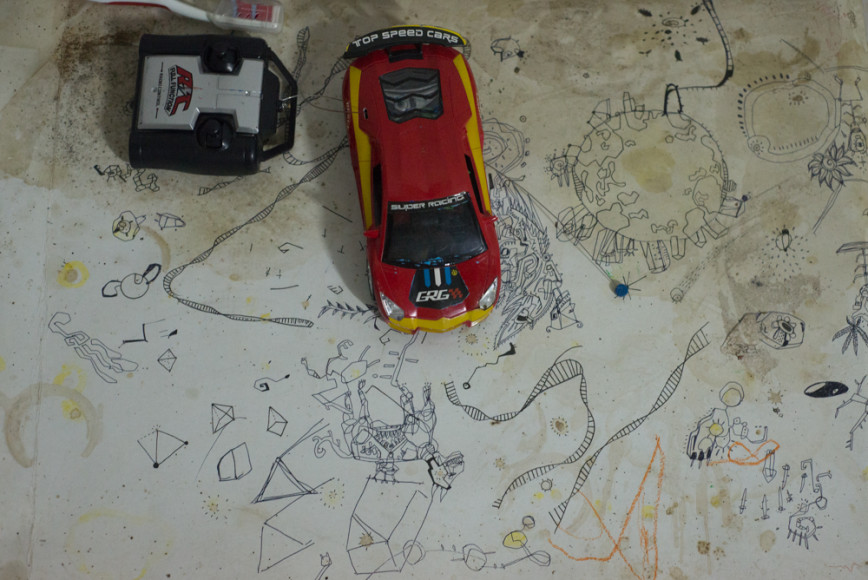

In 2013, I began interviewing and photographing this friend and another individual—both of whom had been released from prison by that time. I photographed the artwork they had made in lock-up and discovered how this art practice had fundamentally changed their prison experience. They had used their adept vision to document the injustices and range of emotions they had felt while imprisoned, and I could see that this had helped them balance external pressures and create multi-layered art out of a traumatic experience.

During my work and interactions, I continually reflected on these questions: what are the effects of locking up drug offenders? Is it changing the offenders, their communities and families for the better?

It is now my vision that the photos I take of these men, their families, and their art practice will help create dialogue about how to make the justice system more functional.

The two men who committed to this project were interested in sharing their stories because they felt that everyone—locally and abroad—should know the realities that prisoners face in Indonesia. They hope that the stigma of drug use and prison time can be transcended in order to focus on the work of making change.

Through my research and conversations with these former inmates in Indonesia, I discovered that they had faced rampant corruption, extortion, and violence in prison. I found that people were often convicted without solid evidence, that they sometimes possessed only small amounts of narcotics or marijuana but were given long drug distribution sentences, while large time dealers got off with lighter sentences. The person with the fattest wallet got the best treatment. I learned that mentally ill people often became police targets, and periodically drugs were planted on them in order for police to meet arrest quotas. Once they were locked up, they didn’t necessarily receive adequate care, and they sometimes created turmoil in the cramped cells they shared with the general population. Many people told me disheartening stories about human rights abuses in Indonesian prisons.

I discovered that my subjects’ art practices helped them transcend the madness of such an institutional setting, with all its turmoil and uncertainty, and reconcile their experiences inside prison with their lives outside. Themes of loneliness, chaos, and frustration were prominent in their artwork and recollections of prison time; yet throwing themselves into creating a record of their experiences and feelings while in prison helped them process all the things they faced, and seemed to sustain them while in a difficult situation. Similar to a person who practices meditation to tackle stress in their life, my subjects’ art practices helped them navigate their unsettled and imperfect lives away from home with some imagination and calm.

Having the chance to meet former inmates, some with drug addictions, has further impressed upon me that this is a human issue, and something that affects us all. I am heartened by the strength people show in navigating the prison system, and then reacclimatizing, in some cases, excelling, at life on the outside. The project has made me even more interested in telling truthful, sensitive stories about everyday people. I’m learning how stigma can truly inhibit growth and I want the climate to change in order to allow former inmates to feel empowered to speak up in a safe way about how they can be supported so they can be a cohesive part of society.

As my project captured my Indonesian subjects’ day-to-day interactions and experiences, I always strove to document with balance and fairness. I worked slowly and revisited my subjects to really get to know them. I photographed them with honesty and kindness because I was aware of their vulnerability. This project will not only be available in Indonesia but it has made its way to the US and will hopefully be shown in other countries. My goal is to depict my subjects fairly.

I want this work to be accessible to people and families who have experienced incarceration as well those who have no prior contact with people who have been imprisoned. I believe photography can give insight into people’s motivations and life patterns, which in turn supports empathy and builds awareness. It is my intention that this project will facilitate dialogue and encourage support for incarcerated people and exiting inmates, so that their community can help them make good choices and find positive paths.

I intend to partner with nonprofits in Indonesia and the US who work with exiting inmates and use this photo series to spur discussion about prison reform and to provide evidence for the need to offer appropriate services to exiting inmates. I am currently researching the continuation of this project here in the US.

My Indonesian friend still struggles. He hasn’t found a good job yet and, even outside prison walls, feels crowded and restricted. The confines of his culture are more evident to him now; he has transgressed and he feels it deeply. He is still on parole and hasn’t been able to get jobs in his field because of his record. But he remains engaged in the arts. He is helping a Yogyakarta village create murals, organize their library and plan handicraft production to help the local economy. Despite his lack of formal work opportunities, he remains optimistic.

All photos are copyrighted by Willow Paule. Artwork is credited to Mawardi and Radilah Amin.